Intentionality And The Preservation Of Art

We invited the curator Rebecca Uchill to present a lecture at Interaccess on October 9, 2014. Specifically, to expand on the ideas and questions posed by the exhibition, Mean Time to Upgrade. The exhibition features artworks selected from a call for “works in existential crisis” due to being on the verge of technological obsolescence.

We first got to know Uchill’s work from a 2010 interview where she discusses the Variable Art Team (VAT), an interdepartmental initiative she co-founded at the Indianapolis Museum of Art. The project was informed by similar preservation initiatives of the same spirit at that time, such the Variable Media Network. The VAT worked with a diverse team (from curators and conservators, to installers and registrars) with the aim of discussing and implementing experimental approaches toward the acquisition and maintenance of contemporary artworks recognized as having variable materials (e.g. installation, time-based or site-sensitive artwork, electronic or media-based art with updating platforms and devices, and conceptual art, ephemeral art, or art made with unsustainable materials). The project was intriguing because, for curators working with variable artworks, one may experience the ways artworks can respond and evolve with the contexts and conditions in which they are exhibited.

In conceptualizing Mean Time to Upgrade, we aimed to take an interdisciplinary approach, inspired by these ideas.

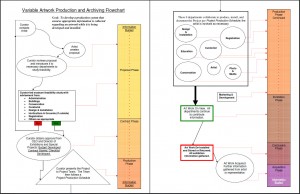

Variable Artwork Production and Archiving Flowchart Rev. 1.1

During our discussions on the topic, Uchill pointed out an article she wrote titled, “Processing Transactions, Forming Intent: Coproduction and Exchange in the Work of Allison Smith” wherein she poses a challenging question to conservators and historians on the role that an artist’s intent plays in determining how to preserve an artwork. Especially when their material aspects are not easily identifiable or evident, such as with participatory, processional or time-based performance and installation work. In the essay, Uchill writes about how ephemeral and conceptual moments of interpretation and exchange that are generated through the collaborative processes of creating and presenting are integral and thus, should be incorporated in preservation mandates: "If the intentional content of socially engaged performance operates between the artist’s intentions, her collaborator’s purposes, and their audience experiences, then conservation treatments should account explicitly for that exchange."

By focusing on the role of artistic intent in conservation practices in the essay, Uchill shows how we can become more clear on the complex roles and contributions involved in the preservation, presentation and life support of variable works that are typically not considered in art historical interpretation. She connects the notion of “original intent” of an artwork with a similar idea of the “original state” of an artwork, putting into relief their limitations when considering the evolving nature of most variable media works. The critique however does not aim to disregard historical phases of an artwork, nor tries to diminish the artist’s voice in any way; rather her text suggests creating, in Uchill’s words, “conservation approaches and curatorial reportage that recognizes collaborative facture and divergent motives as inflecting and strengthening art conservation and history.”

It’s probably worth discussing why the conservation and historical practices in art would be of interest to InterAccess, being a non-collecting institution; or how a case study such as Allison Smith’s work—a participatory art practice without clear technological components—would relate to the new media focus of our mandate. Some initial thought on this:

- Participatory works such those discussed in Uchill's article and new media works have a lot in common. First in how their material components are not self-evident upon first look, the way it might be with traditional painting (canvas, paint, brush, painter) or sculpture (e.g. wood stone, marble, sculpting tools, sculptor), and therefore the "original state" is more difficult to define.

- There is a common element of "interactivity" in these works, having been comprised of so-called, non-passive qualities (gesture, confrontation, interactivity, invitation to participate/respond/play).

- Another term that is referenced in the article that we could use to describe the common aspect of durational works like Smith and new media works is, “the expanded field”: artworks constituting new forms that do not fit into the closed binary of art and non-art. (A great article that itself expands on art critic Rosalind Kruass and Hal Foster’s seminal writing on the topic in relation to “social media” art can be found here). The point Uchill makes is that the process of making works in this realm should be taken seriously: “…the ways that works of art are shaped in the expanded field should be significant for the production and preservation of material culture…”

- Being a non-collecting institution that supports the creation, advancement, dialogue and presentation of new media artworks, InterAccess’s approach cannot be based on conservation in the usual sense, as we do not have a collection nor do we have the infrastructure for maintenance or conservation services. However, any number of gallery staff, contract installers, curators, audiences, as well as architecture, climate, noise levels and even neighbours can have a lot to do with the exhibition of an artwork, in some cases even actually change their integral “properties”. In this regard, the perspective that Uchill brings in her article has affinities with the processes in which InterAccess and other non-collecting and collecting art institutions alike are involved.

What modes of thinking could be developed in relation to an expanded field of factors not typically considered in the presentation and preservation of an artwork's life? How might this relate to technological determinism, planned obsolescence, and the divisions between form/content, technology/nature?

Banner Image, courtesy of Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design: Egyptian, Old Kingdom, Dynasty 6, 2400-2250 BCE

Head of a man, 2400-2250 BCE